From 1st to 12th grade, students across the globe are taught to focus on their grades, so that they can succeed in the future. From freshman to senior year many students are scolded and scorned to focus on their grades to get into college in the future. From a young child to a maturing young adult, students are taught to steadily improve their grades; to strive towards that one hundred percent: a clear depiction of perfection.

In a world where academics are slowly but surely determining a student’s worth in the future, whether or not young adults get into good colleges, the hyperfixation on grades and performing your best in academics forces many students to lose sight of themselves and their true individuality. In the underlying pursuit of many towards high grades, prestigious degrees, and successful futures, many students unknowingly sacrifice a key aspect of their identity — themselves.

At Norwin High School, the administration strives towards success in all fields: from sports to academics to leadership. However, the broad school system in America and across the world all revolves around the same, sometimes diminishing, system: one focused solely on a student’s performance in terms of letter grades and numbers. From a very young age, students and children are taught that grades are directly proportional and comparable to their future and successes. For too many young students, A’s are seen as representing impressive academic achievements, whereas F’s are seen directly as “failure”. The underlying connotations of “A’s” and “F’s” can directly affect someone’s mental well-being and the perception of themselves.

In a recent study from Queen’s University, the modern system of grades is seen as the “primary currency of learning.” In this sense, the direct resemblance of grades to a monetary value in life, having the same purpose as granting new beneficial feelings or emotions to the student who received good grades, can be very diminishing. To many students, the halls of Norwin High School, and throughout the globe as a whole, money can be seen as buying happiness. Whether this is new clothes or even a small piece of chocolate, money can grant happiness to a person. Similarly, grades and A’s on assignments may directly correlate to feelings of happiness, either stemming from parents, peers, or a sense of fulfillment in your own life and purpose.

As a result of seeing grades as a form of currency, promoting feelings of self-worth and fulfillment, many students might strive to focus intensely on grades to achieve a falsifying purpose. In reality, many studies suggest that students from the age of 5 to 18 should be focused on developing hobbies and understanding their likes and dislikes, before intensely focusing solely on numerical values like grades. Instead, many students who strive towards success and fulfillment focus on grades because it is the only form of criticism that they can attest to and potentially fix in the future.

According to the Oxford Specialist Tutors, hyperfixation can be defined as the “intense focus on one thing to the exclusion of everything else.” In many cases, because so many students identify their grades with their self-worth in the world, many high-achieving students might lose sight of the world around them and their true hobbies due to a focus solely on grades. When completing assignments or even looking over an exam, many students tend to hyperfixate on making sure that all of their answers are deemed “correct.” In a world where there is often only one “correct” answer in subjects like math and science, a majority of students focus on attaining this “correct” answer to achieve a sense of self and achievement.

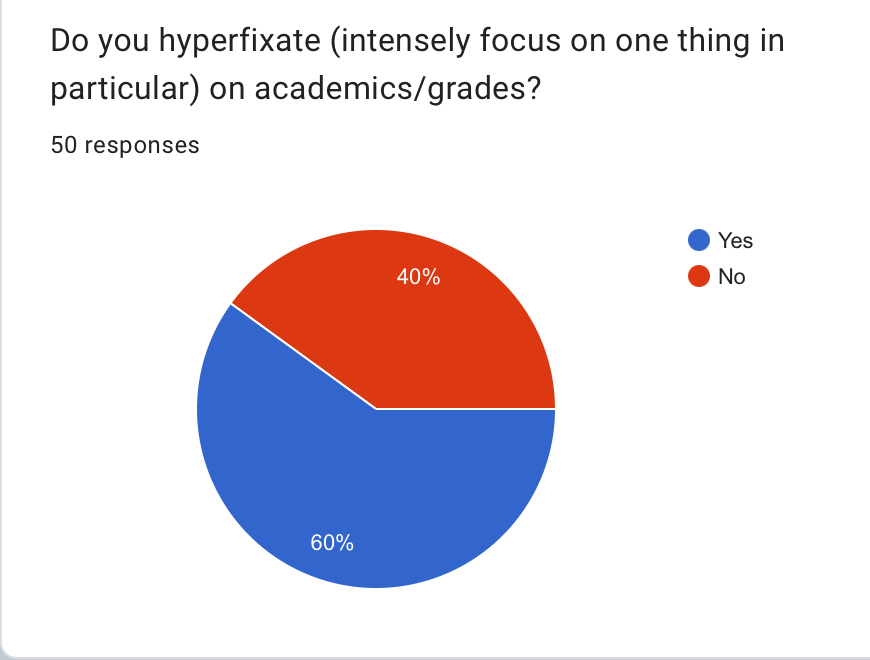

In a recent Norwin poll, conducted by over 50 students at the high school, about 60 percent of students said that they hyperfixate on grades and academics. Therefore proving that academics and grades play a big role in a student’s life on a daily basis, perhaps more than they should to the point of an exclusion of other important hobbies that help to build a career path.

Even though the results of the Norwin poll are not too drastic, a point is still proven when looking at the 60 percent of students who admitted that they do hyperfixate on academics: several students spend a wide majority of their time completing academic work, contributing to the potential loss of important hobbies.

For many students, they lose sight of important hobbies or sports due to high school: the nature of a level-up when it comes to academics. Over 80 percent of students reported that they hyperfixate on academics because of self-pressure and an inside urge towards achieving ultimate perfection. From a first look at why students hyperfixate on academics and grades, one might think that the pressure is ultimately derived from parents or peers: disguising itself as an inner strive towards perfection and an inner competitive nature of today’s generation. However, many students strive for perfection in academics because they feel like it is the only “grade” that they can rightfully attest to.

“I feel like I need to prove to myself that I am good enough,” said junior Theo Summers. “Although I know I am a smart person, I hold my breath hoping that one test grade is an A. It is draining, but it is the basis of my mental ability.”

Ultimately, this fear of grades and failure being deemed an “F” results from giving grades too much importance. Over the years, many studies have found that grade inflation has slowly been taking over the academic environment (EducationWeek). Students GPA’s are climbing remarkably due to the leading competitive nature of college, ultimately causing students to become more and more stressed about grades. This pressure usually does not stem from parents or parental figures in life because colleges at an earlier age were much less competitive compared to the modern age. Additionally, many students feel the need to perform well at school to prove their worth to the world and to stand out and say that they are important and valuable.

Jillian Ryba, a freshman at the high school, noted that she felt very pressured to perform well in school due to performing well all of her life. Ryba also admitted that she even quit some important hobbies to focus more on school since the start of high school.

“I have always felt that since I have done so well in school, it is expected that I meet unrealistic and impossible standards,” said Ryba. “My grades run my life and make me sacrifice a lot, especially sleep. No one has ever pressured me to crave academic validation, but I do, and I feel like when I mess up and do not perform as well as I usually do, people forget that I am human.”

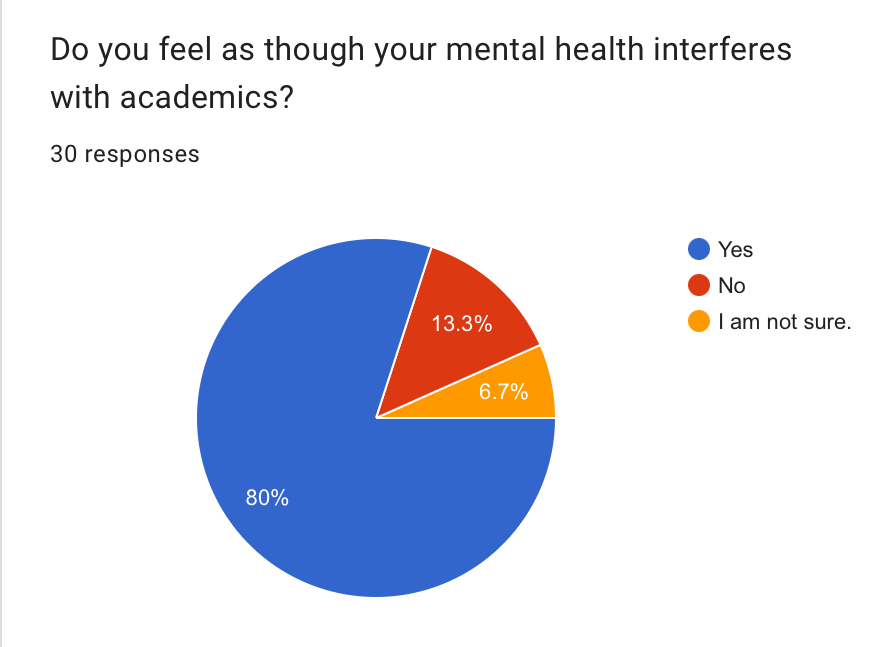

From a very young age, it is clear that grades determine more than just the classes that you will take next year, they also play a role in determining your self-worth and overall future in college and a career. In many cases, students’ mental health frequently interferes with academics.

Clearly, this variety of students who admitted that their mental health plays an important role in school is concerning. It is not usually normal for students to experience this much stress coming from schoolwork alone. According to an article from the Harvard Business Publishing Education Program, many students “fear the possibility of failure rather than focusing on the possibility of learning.”

In an environment that is supposed to be dedicated to learning new information, many students find that the halls of Norwin High School are filled with more pressures and stress than actual learning activities. For many students, their mental health might depend on how well they perform in school because they directly correlate their mental well-being with numerical values that appear as grades on a transcript. The connotation behind an “F” implies direct “failure” contributing to feelings of self-doubt rather than boosting your confidence more.

“When I get a bad grade, I feel like a failure and that test or assignment becomes the only thing I can think about for weeks,” said Ryba. “My emotions affect my grades because when I am stressed about school, I am sometimes disrespectful to those around me because all I can think about is that one grade.”

When students focus intensely, or hyperfixate, on academics and grades determined by their writing or test performance, they might feel inclined to focus only on performing well on that assignment, contributing to a standoffish attitude towards others. People who focus intensely on grades might appear rude to others who value social interactions in the classroom more than grades. Ultimately, this can contribute to labels and stereotypes of “smart students.” Many smart students are labeled as being extremely quiet or being called a “nerd.” In many cases, students feel like their emotions affect their grades, contributing to a more stressed attitude during school time.

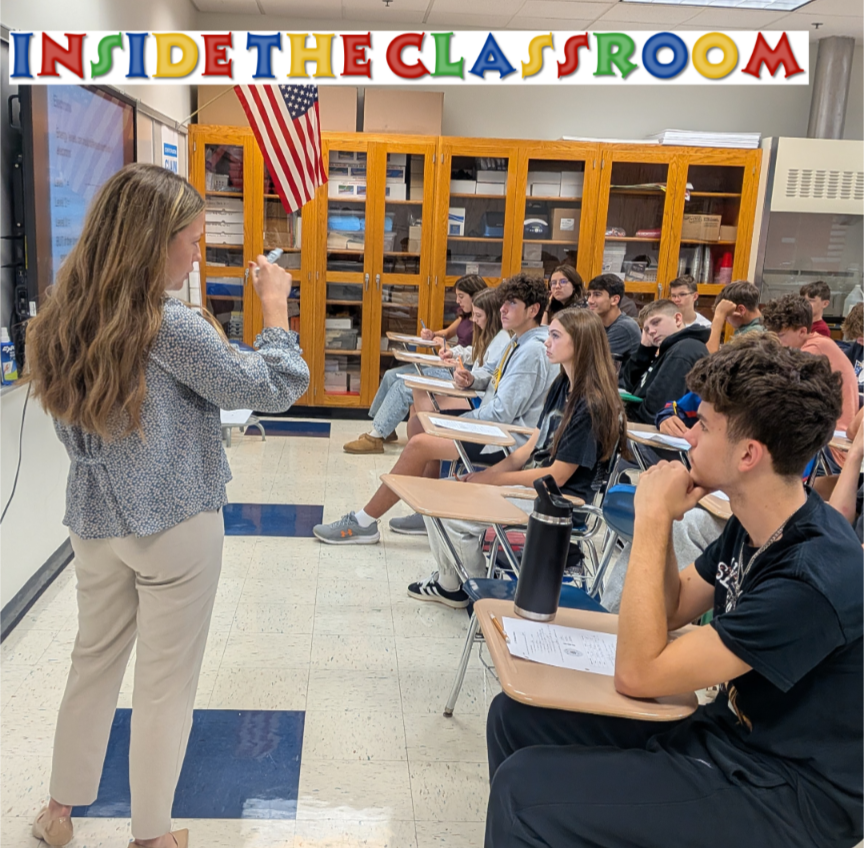

Mrs. Kauffman, the school librarian and one of the gifted case managers at Norwin High School, sees a lot of students regularly in the library. From asking to print an assignment out to asking where materials are for an art project, Kauffman observes many students stressed over academics, and other students regularly chatting and not caring too much about their grades.

“I see a pretty good mix of students collaborating with friends and classmates and working or relaxing individually in the library,” said Kauffman. “The problem is that the same students are always studying or always chatting – again, finding that healthy balance would benefit students.”

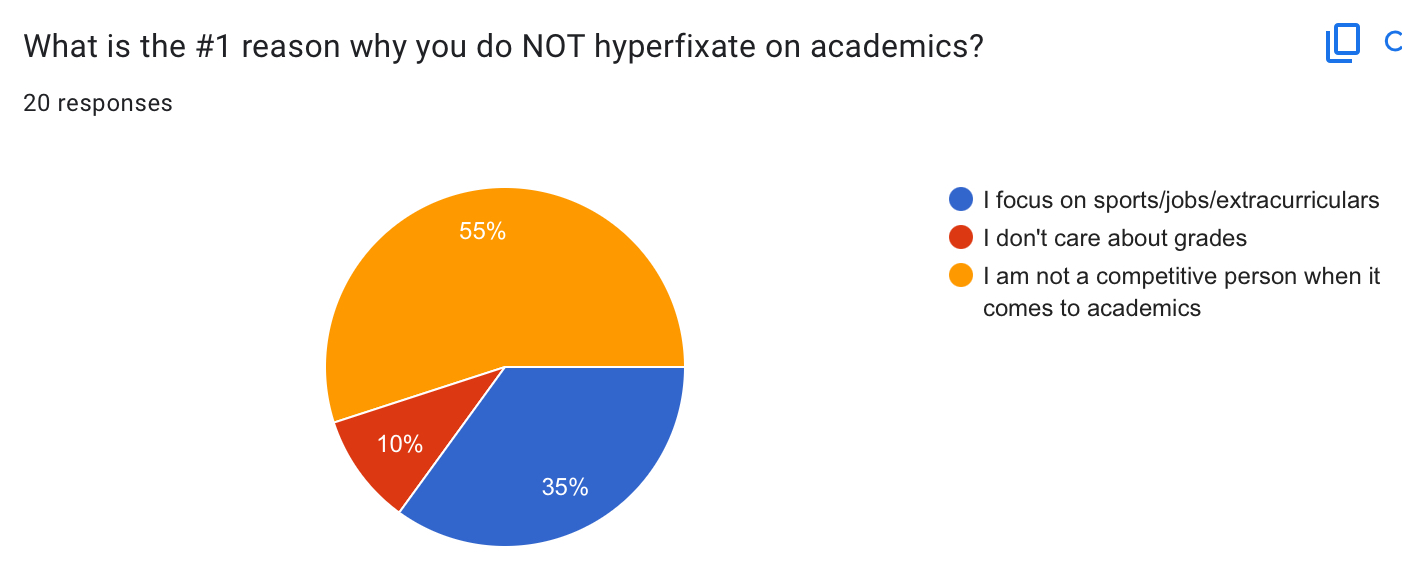

Every day of school, many students constantly strive towards that 100 percent on an assignment or as close to an “A” on an exam. However, others appear to not hyperfixate nearly as much on grades. Over 55 percent of students in a recent poll that answered “no” to whether they hyperfixate on academics reported that they do not hyperfixate on grades because they are not competitive when it comes to academics.

In today’s world of increased technological advancements and a media-filled environment, many students might lack a drive or internal source of motivation toward academic performance because of the slowly growing performances and sights of AI that help many students cheat effectively and not care as much about school assignments. On the other hand, many students in today’s society might strive towards trophies when it comes to academic achievements. James Tobin, a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist who researched the silent epidemic of a loss of identity in today’s generation, reported seeing a “dimming of identity” in teenagers and a “capacity to be alone.”

Resulting from COVID-19, many students became more acclimated to an environment characterized by Zoom meetings and online interactions. Therefore, when returning to school from the epidemic, many had an inner “capacity to be alone” because of such a long time spent away from any sort of social interaction. When students returned to school, many became more isolated. Some students even believe that school forces you to isolate certain hobbies because school learning has become more formulaic.

“I believe that school encourages you to isolate parts of yourself to fit the mold that the school wants you to be,” said junior Theo Summers. “It’s hard to find a sense of self in school because you are forced to be a cardboard cutout of what the teachers, administrators, and other students want you to be.”

As a result of grades and academic course loads becoming more and more important in the college admission process, many students have started to define themselves based on the courses and grades that they receive. In a recent poll, over 75 percent of Norwin students identified with the “Self-Conscious Personality Type” out of many self-estrangement personality types identified by clinical psychologist, James Tobin. This personality type defines students, mainly high schoolers struggling through their formative teenage years, as being “engrossed in what is expected” of them and seeing themselves as “never ‘good enough’ as others” around them.

In today’s modern world being “good” at school is expected by many students. Because of inflated grades and higher college admissions, schooling has become a key aspect of teenagers’ identity, defining if they are worthy of a valuable future based solely on their grades and performance.

There are many different types of intelligence, beyond simply being good at school. However, those who find themselves hyperfixating on school and grades often lose sight of fulfilling other important aspects that define their individuality: certain hobbies, relationships, and understanding themselves and what they want to do in the future.

Out of the 60 percent of Norwin students who said that they hyperfixate on grades and academics, it is important to realize that grades and “A’s” on assignments do not correlate perfectly to greatness. The shackles of academic hyperfixation must be broken, for students to rediscover and embrace their true selves that many lose due to the harsh connotations of grades.

From childhood to young adulthood, focusing on achieving 100 percent regularly can be very diminishing. Students must learn from mistakes and failures to propel forward in life, however many are forced to reject failure because of the underlying stigmas of being bad at school. From 1st to 12th grade, it is important to recognize that grades do not define our entire existence. Young adults must focus on more than just grades, to break free from the shackles of academic hyperfixation to allow students to rediscover their true selves instead of being defined by solely grades and academic performance.