Education is often credited as an equalizer, something that provides every child with an opportunity to succeed. Yet it is the unfortunate reality that economic disparities between school districts, and even within individual schools, create stark differences in educational opportunities available to students- an issue that is especially prominent in the Pittsburgh area. From underfunded schools struggling to provide basic resources to low-income students, to high-income districts feeling excluded from enrichment activities, the reality of education in Pennsylvania is far from equal.

Education is often credited as an equalizer, something that provides every child with an opportunity to succeed. Yet it is the unfortunate reality that economic disparities between school districts, and even within individual schools, create stark differences in educational opportunities available to students- an issue that is especially prominent in the Pittsburgh area. From underfunded schools struggling to provide basic resources to low-income students, to high-income districts feeling excluded from enrichment activities, the reality of education in Pennsylvania is far from equal.

Pennsylvania’s public school system is one of the most inequitable in the country, with districts relying heavily on local property taxes for funding. This creates a system where wealthier districts can afford better facilities, more experienced teachers, and a wider range of extracurricular activities and academic programs, while low-income school districts still struggle to provide the basics.

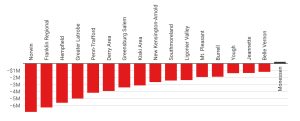

For instance, the Jeannette School District, one of the lowest-income districts in Westmoreland County, has a vastly different educational experience than Norwin, a notably more affluent district.

“Everything we want to do that could better our education costs money,” a student from Norwin expresses the frustration they see between their school and others in the area. “My cousins live in Jeanette and have to pay to do absolutely anything in their school. It’s like the Pennsylvania education system feels like impoverished schools don’t deserve the dancing for things that could further one’s education experience. It’s completely unfair and needs to be fixed.”

Sentiments such as these highlight a systematic issue. Students in lower-income schools not only face financial barriers but also a lack of investment in programs that could enhance their learning.

Schools with lower funding often struggle to provide adequate educational resources, which can impact student performance. According to Public Source, during the 2022-23 school year, only 8 percent of students at Westinghouse Academy scored proficient or advanced in math, and 29 percent in English. District-wide, the numbers were only slightly better, with 25 percent proficient in math and 52 percent in English.

These performance issues are not a result of a lack of student effort. According to the Allegheny Institute of Public Policy, Pittsburgh Public Schools spend about $30,000 per student, which is one of the highest per-pupil expenditures in the state. Despite this statistic, other socioeconomic factors influence educational outcomes. Students in low-income areas often face additional challenges such as food insecurity, unstable housing, and enrichment programs.

The racial disparities in Pittsburgh’s education system also highlight these inequalities. According to the National Equity Atlas, 92 percent of Black students in Pittsburgh attend low-income schools, compared to significantly lower amounts of white students.

According to Matthew Kelly, school funding expert and Penn State College of Education professor, the funding shortfall of Pennsylvania schools is more than $4,000 per pupil. Even with this statistic, economic inequities in education do not only affect students in low-income schools. Even in well-funded districts like Norwin, students from lower-income backgrounds face challenges that their more affluent peers do not. One student shaped their experience of transferring from a lower-income school to Norwin-

“Before I moved to Norwin, I went to Propel in Turtle Creek, and there were a lot of income problems there,” said one current Norwin student on a recent Knight Krier poll. “Kids would not be able to go on field trips or watch the movies for class or bring in stuff for projects.”

Even in Norwin, where funding is significantly higher than in many other districts. Many opportunities, such as AP courses, Model UN, athletics, and more, come with costs that are simply not affordable for all students.

“I wanted to participate in Model UN or theatre, but my family just doesn’t have the money for it long term,” another Norwin student states in the poll question about financial barriers to education.

These barriers create a two-tiered system where wealthier students can take full advantage of extracurricular and academic opportunities, while lower-income students can miss out. This exclusion can have lasting effects, even limiting college and career opportunities.

Economic disparities in high school do not just impact students in the present; they shape their futures. A recent poll of Norwin students found that 76 percent of students believe disparities in resources and opportunities at their school could negatively impact their chances of getting into college or finding a suitable job in the future.

Research has shown that students from wealthier backgrounds have better access to college prep resources, advanced coursework, and extracurricular activities that make them more competitive applicants. In contrast, students from lower-income families often face challenges such as being unable to afford SAT prep courses, college application fees, or even AP coursework fees. This creates a cycle where wealthier students continue to have access to better opportunities, while lower-income students struggle to free themselves from lifelong economic hardship.

Addressing economic inequality in Pittsburgh-area schools requires systemic change. This can include reforming school funding, increasing access to free extracurriculars, providing additional support for low-income students and addressing racial and economic segregation in schools.

Pennsylvania’s reliance on property taxes for school funding creates an unequal system. A shift toward more equitable funding usage, where state funding is distributed based on student needs rather than local wealth, could help ensure all students receive a quality education. Schools should also work to eliminate or reduce costs associated with extracurricular activities, AP exams, and field trips. Partnerships with local businesses and nonprofits could help provide funding for students who cannot afford these costs.

The economic inequities in Pittsburgh-area schools are not just a problem for low-income students—they are a problem for society as a whole. When we fail to provide equal educational opportunities, we limit the potential of countless students and deepen the cycle of poverty.

The students who recognize these disparities are calling for change. Their voices highlight the urgent need for reform. Every student, regardless of their zip code or family income, deserves the opportunity to succeed. If we truly believe in education as the great equalizer, we must ensure that it lives up to that promise.