Shut Up and Dribble

Racism has always been on the forefront of national discussion. Why, then, are those who regularly grace a public stage excluded from this conversation?

LeBron James, Tommie Smith, John Carlos, Colin Kaepernick.

Colin Kaepernick lowers his knee gently to the turf.

The ground beneath him stays silent, but the thousands of onlookers are anything but. They represent centuries of oppression, thousands of years of forgotten history, and a challenge for athletes across the world. The man beside him, his teammate Eric Reid, represents the solidarity that will keep him going for as long as he can, even when the fans, the media, and the President of the United States of America offer their harshest criticism and opposition. He doesn’t know it yet, but his actions will inspire millions to speak out against social injustice. In retrospect, though, it seems his knee is taken in vain.

From the standpoint of an American citizen, this narrative is played out. For the last four years, it’s been a repeated point at dinner tables, news outlets, and talk shows across the country. Colin Kaepernick has become a household name, and for good reason. During the last season of his sporadic, yet successful NFL career, the quarterback decided to protest police brutality by kneeling during the national anthem, which had seemingly every person in the nation forming an opinion about his actions, ranging from embracement to downright condemnation. Four years later, he’s still out of a job, a reality that a majority of the population has come to accept as a final resolution.

That doesn’t necessarily mean the fight is over, though. The hectic Trump presidency, as well as the tragic police altercations involving George Floyd and Jacob Blake, reinvigorated the protesting spirit of athletes across the country, with kneeling for the national anthem and other forms of opposition to the current state of affairs becoming increasingly popular. One of the most famous instances of this was the comments of Lebron James in a 2018 interview, where he remarked that the “#1 job in the nation” is held by someone who “doesn’t understand the people.” It took only hours before the media started to attack James, with Laura Ingraham famously telling the athlete to “shut up and dribble.” This incident took the sports world by storm, as many public figures took to social media to defend James, but unfortunately, some don’t realize the bigger, inconvenient truth behind the controversy: this is not an isolated occurrence. This is a continuation of the lengthy history of black athletes being persecuted for speaking out against social injustice.

The history that I’m referencing is not one with a beginning and an end. The origins of racism and segregation can hardly be traced, and as for their footprint in organized sports, they have been a fixture from the beginning. Despite the terms of the Emancipation Proclamation, most Americans held on tight to their discriminatory, pseudoscientific theories deep into the twentieth century, and the presence of color barriers in major sports leagues was proof of just that. Jack Johnson, arguably the most dominant fighter of his time, was famously refused a fight against then-World Heavyweight Champion James Jeffries in 1907. Three years later, when Jeffries finally reconsidered, he was promptly given the nickname “Great White Hope,” as he was expected to beat Johnson, despite being severely out of shape. Fifteen rounds later, Johnson was clearly in control, but for reasons that can only be inferred, referee Tex Rickard stopped the fight before Jeffries was knocked out for good. Such was the procession a century ago, and the fight for equality was unfortunately a grueling one. It took influential black athletes like Jackie Robinson and Jesse Owens to achieve integration, and despite their achievements, the fight is not even close to done. The reason that athletes like Robinson were able to break the color barrier was because of their silence toward oppression. Despite the unspeakable challenges they faced, the right to speak out against social injustice was not granted to them, and in the decades that followed, the numerous athletes who disregarded the terms of this social custom were met harshly, to say the least. I am America. I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me – black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own. Get used to me. — Muhammad Ali

Perhaps the most famous example, besides Kaepernick, is Muhammad Ali. Although he is celebrated now, many forget that during the peak of his boxing career, he was one of the most hated men in America. Until 1964, he was known as Cassius Clay, but after joining the nation of Islam, he changed his name and, in a more controversial move, refused to fight in the Vietnam War. At a time when patriotism, as well as its dangerous relative, nationalism, had taken firm root in the United States, this was an unfathomable choice. To disrespect the values of his home country was one thing. To do that loudly? As a black man? As someone whose religion was unfamiliar and downright frightening to the people of his nation? When all was said and done, he was lucky to still be alive.

As for his contemporaries, Ali has dozens. Injustice emanated from the 1960s like no other time, and the pushback, though scarce, was loud and assertive. Two such examples, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, are responsible for one of the most infamous moments in Olympic history; during the 1968 Mexico City Games, after the two athletes medaled in the 200-meter dash, they made black power salutes on the podium, holding up their fists during the playing of the National Anthem. Unsurprisingly, the vilification they faced was swift and furious. Avery Brundage, the longtime Chairman of the International Olympic Committee, forced the United States to expel both Smith and Carlos from the Olympic Games, describing their actions as “a schoolboy prank” and remarking that “the boys were sent home, but they should not have been there in the first place.” White America would not understand. They recognize me only when I do something bad and they call me ‘Negro.’ — John Carlos

When the athletes arrived home, the trouble only escalated, as a wave of death threats floated their way. No names were attached to these idle promises, but in the grand scheme of things, that really didn’t matter. The metaphorical warrant for the death of these two men was not signed by a small mob of angry citizens. It was ratified by an entire country.

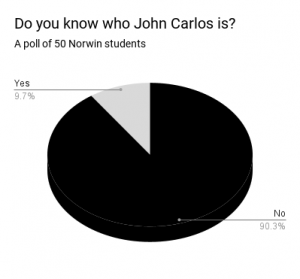

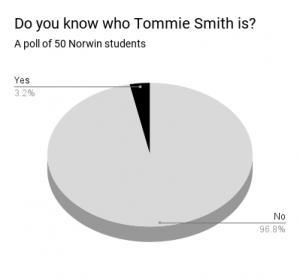

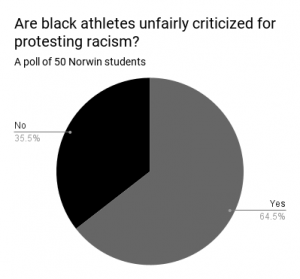

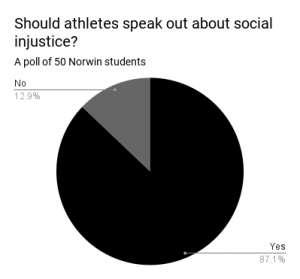

Condemnation is expected, though. America has presented a face of bigotry more times than can be outlined in one curriculum, and the recognition of this by some of the country’s most influential figures is met with harsh criticism. This has been established; the deeper problem lies in ignorance. The younger generations deserve to know the tales of the brave souls who have dared to challenge the backward tradition that is silence in the face of injustice. They deserve to know the flaws of their country. Evidently, though, this knowledge has not graced the children. In a survey of 50 Norwin High School students, only 10 percent of responders said that they knew who John Carlos was and what sport he played. For Tommie Smith, that number was 3 percent. Only those who care to explore the past objectively will find its most hideous details; public education will never reveal them.

When you combine ignorance and condemnation, you ultimately end up with discouragement. Right now, the general public sees the examples of Colin Kaepernick and LeBron James, and they see men who have suffered for their actions. Meanwhile, when they see Jackie Robinson, a man who held his tongue because that was his only choice, they see a hero. This is actively encouraging and perpetuating silence, a dangerous trend that, if continued, will lead to a future similar to the past: a future where the First Amendment has lost its value, where the right of opinion is left to those who acquire their knowledge on the issues that pervade our country through artificial means instead of the citizens who live them, who experience them every day. This is the future that appeals to a threatening amount of individuals.

Luckily, there is still hope. Some people see that this is wrong, and that it is worth fixing. Jayden Walker, a senior at Norwin High School and a fellow black athlete, is one of those people. In a recent interview, Walker discussed his thoughts on black athletes speaking out against social injustice:

“Athletes nowadays are looked up to, in some cases, more than a lot of ‘A-list’ celebrities, and I feel like they have more of an important opinion on things, and they should share them,” said Walker. “These kids like me will see them and know what they represent. Issues like racism are so big right now, and these athletes have the chance to make them bigger and more widely known to the common people.”

Luckily, Walker has not encountered racism in his life, and he has not utilized any methods of speaking out about it. He does acknowledge it, though, and if the time comes, he is ready to speak.

“I haven’t dealt with it yet, so I haven’t had an opportunity to speak out on it,” said Walker. “If it would happen, though, I would definitely speak out on it.”

There are many athletes, though, who have witnessed racism firsthand, and when they do take this “opportunity” that Walker describes, they are often criticized, and the reason that they face such criticism is hotly debated.

“I think people just don’t like seeing change,” said Walker. “A lot of times, they don’t see the racism, but in reality, it’s here. But they don’t want to see anyone speaking about these ‘people’ issues instead of sticking to their sport.”

In essence, that is the counterargument. The idea that politics in sports distracts from the game itself is the rallying cry of nearly everyone who condemns athletes for speaking out. Walker, though, brings an interesting rebuttal:

“I would say to these people, put yourself in that situation. I think you’d be doing the same thing,” said Walker. “If something bad is going on in the world, I don’t think a sport should be able to shut you up and make you not be able to speak what you believe.”

As for the example of Kaepernick, his particular methods have proven to be more polarizing to the American people than nearly any issue in today’s politics. His choice to kneel for the flag has everyone picking sides, and for every point made, there is a counterargument.

“Some people will say, ‘Oh, look at what they’re doing, they’re hurting the troops, this isn’t the right time,'” said Walker. “In reality, though, I think it is the right time to protest, because now it gets our attention, and he’s bringing light to these issues. It’s important for him to be that pioneer.”

Like the pioneers of the past, though, there’s a good chance that Kaepernick will one day be forgotten. He will continue to remain jobless, an activist with no hope of continuing his once-great career. When he dies, it will be up to us to pass on his legacy, but at this rate, it’s doubtful our grandkids will know his name, despite the monumental impact he made upon society.

“It’s important to remember these people,” said Walker. “They deserve to be known just as much as a president from older times for the change they are helping to make happen.”

If we do start to have more remembrance, a positive consequence will be a future in which athletes are encouraged to make their voices heard. These issues will never fade away, and as long as they’re here, it’s important to have influential figures going to war against them.

“I don’t think this movement against racial injustice will ever stop,” said Walker. “Not everything in the world will be perfect, but to show people what’s really going on, I think that’s the right thing to do.”

That simple action – doing the right thing – is our only defense. Racism may pervade society as long as we live. Hundreds may die each year at the hands of police brutality, and thousands more may struggle to get ahead as systemic racism continues its chokehold on America. The act of speaking out against these terrible continuities may continue to be criticized. All of those realities are out of our control for now. The only thing you can control is yourself. When someone tells you to shut up and dribble, you cannot change their opinions. The only thing you can do is defy their orders and continue to speak for what you believe in.

Every conversation has to start somewhere. If we can’t do that, then who will?

— Jayden Walker

Oliver is a senior, and he has been a part of the newspaper staff for 3 years. He covers a wide range of topics, from school news to student features,...