What’s in a streak?

Snapchat streaks are a common internet trend that have the public split in opinion. Why do so many teens go out of their way to keep them?

Keeping streaks seems like a trivial habit, but psychology tells us that there are some benefits.

In today’s society, we hear the term “empty gesture” more than ever, evaluating the various actions we take every day that aren’t based on practicality whatsoever. We do these things all the time, even if we don’t realize it; who among us hasn’t worn a lucky hat or shirt, avoided the unlucky number 13, or otherwise gone out of their way to perform some weird ritual or tradition? These actions are shaped by thousands of years of human behavior, which we like to call culture, but on a more fundamental level, they are shaped by our own psychology, and because of this, we are allowed to ask: “Why on earth do we do these things?”

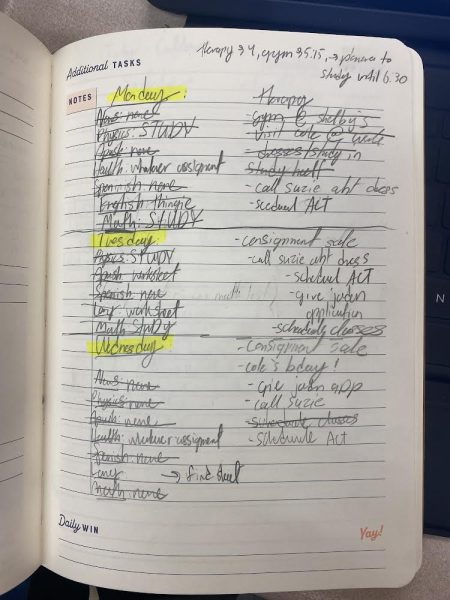

Take the ever-popular Snapchat streak, the basis of which is as follows: users must send a quick picture, typically with the word “streaks” typed on it, to another user at least once every 24-hour period in order to keep a streak going. When the streak reaches three days, a number with a flame appears next to that person’s name, and the number increases with time until the streak is broken. Seems trivial, right? Every day, millions go out of their way to take a picture of nothing, slap a quick label on it, and deliver it to their friends, all to keep a number going. A flame. A cute symbol. These are habits with little thought, little time, little benefit. So why do we do them?

Take it from a teenager with 62 streaks: the question is not resolved. We hope for a simple answer, but we are often left grasping for straws. After all, there’s a lot of complex reasoning that goes into our actions, and the best we can do is take an educated guess with what we collectively know.

In some sense, we can say that we do these things to satisfy our minds; humans have an innate desire for comfort, and our habits and traditions are among the various methods we use to achieve it. The security of knowing our next step can make us less worried about our daily lives, while the idea of change often makes us want to curl up into a ball. In fact, a 2010 study by Northwestern University tells us that we can predict 93 percent of our future actions, and by what we know from psychology, this can even be brought down to a neurological level. Our “reward pathways,” which release dopamine in the brain, are often triggered by actions that we’re familiar with, something that can lead to the formation of habits, good and bad alike. Streaks, to be sure, are no exception; it can often feel relieving, even cathartic to snap a quick picture once a day to keep the cycle going.

“There’s a certain familiarity we have with structure and schedule, and we feel comfortable with that structure and schedule,” said Mr. MacLaughlin, AP Psychology teacher at Norwin High School. “We like it because we can adjust to it and accept it. If we know what’s coming, then it helps to prepare us… we can prepare accordingly, and I think that helps with being less anxious and knowing what to expect.”

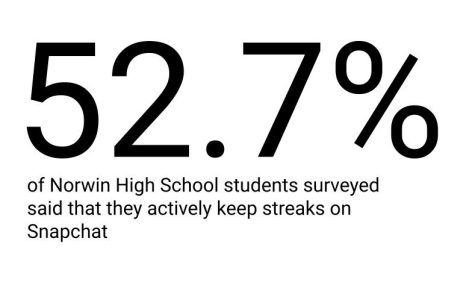

In a high school setting, it’s easy to see how widespread this movement has become. In a recent survey of Norwin High School students that use Snapchat, over half said that they actively keep streaks with their friends, with over 40 percent saying that they keep more than 20 of them.

“Streaks help to keep in touch with people I don’t get to see often,” said an anonymous respondent. “[They] make texting like a competition, but it’s also something tangible to put on something as complex as friendship.”

Streaks can serve as a medium for social interaction where there would otherwise be no reason to communicate, or perhaps no possibility. In a broad sense, social media has often been touted as promoting socialization among teens and young adults, and as the world becomes more interconnected day by day, it allows us to reach thousands of miles with the click of a button. In a study by the University of Missouri School of Journalism, participants who used social media across a 3-year span had an increased feeling of social well-being, evidence of the larger community that our actions help to contribute to.

“I think in some weird way, streaks are like a form of connection between you and another person,” said a Norwin respondent in recent poll. “It’s nice to feel that you’re not totally alienated from another person.”

In contrast, though, many have criticized the shallow nature of keeping streaks, often citing the lack of any palpable benefit. Nearly half of the respondents to the student survey answered that they did not keep any streaks, and several of them asserted that they were, in some way, meaningless. “Streaks hold no relevance… a number shouldn’t justify how you associate yourself with a person.” — Anonymous

“I don’t know what we’re racing towards,” said MacLaughlin. “We want that recognition, we want that acknowledgment, but in that same token, it’s never going to be enough. If you have a streak of 2 or a streak of 2,000, it really doesn’t matter all that much.”

In the past few years, the popularity of streaks has grown simultaneously with a greater reliance on social media and technology as a whole, a topic that has sparked some hostile debate. As easier methods of communication have surfaced, they have started to replace some more old-fashioned practices, and while our lives may be much more convenient now than they ever were, there’s certainly an argument for the benefits of face-to-face interaction.

“It [Social media] disconnects us from the personal aspects of society and the personal aspects of a relationship,” said MacLaughlin. “We tend to seek out personal relationships even less because they can be difficult… it can be very difficult to engage in a conversation.”

Additionally, several studies have shown links between social media and mental health problems, which comes in large part from obsession. The idea of “FOMO,” or the fear of missing out, creates a craze in some people, occasionally leading to drastic action. Users will frequently pass off their login credentials to friends in the event that they are away from their phone and unable to preserve their streaks, a mistake that flies in the face of all the online responsibility lessons kids are taught nowadays.

“It’s almost like it’s addictive after a period of time because there are brain chemicals that are released when we do things that make us feel good,” said MacLaughlin. “That dopamine can be released whether we are eating a big piece of chocolate cake or gambling or drinking alcohol; it’s the dopamine that’s released along that reward pathway in our brain that makes us feel good so we continue to do those things. It acts almost like an addictive substance.”

When we examine the habit a little further, it seems like any other addiction. It’s been established that the benefits, while arguable, are contested by some pretty serious drawbacks, and yet so many of us continue to do it without thinking. Even someone like me, who has enough self-awareness to write this article, is still currently keeping dozens of them. What’s interesting is, as much as we are trying to grow our numbers higher and higher, it can also be said that we are deathly afraid of letting that number go back to zero, a kind of quasi-withdrawal.

“You have to do it tomorrow, because if you don’t do it tomorrow, then it’s all gone, and that would be devastating,” said MacLaughlin. “It’s so easy; all you have to do is put one little thing out there, and if you just put it out there, then you’re one step closer to ‘winning’, and the game is one of the stupidest games you can play because there will always be someone out there with more than you.”

So, yet again, why are they still around? I likely won’t be giving up my streaks anytime soon, despite what we’ve learned here today. People can give a million secondary reasons as their own explanation, but in the end, there’s a strictly human element to examine. The definition of the word “streak” itself has no pertinence to a habit, or to continuity. It is defined as “a long, thin line or mark different from its surroundings,” and while this interpretation refers to the physical meaning of the word, such as a streak of paint on the floor, it actually serves us quite well here in the figurative sense. It’s what all of these rituals are, after all: a celebration of something that stands out. Take the fact that for 37 straight years, a teammate of Shaquille O’Neal had made the NBA Finals. Whether the streak continued another year or not had no direct importance on our lives, but anyone that knew about it had a minuscule, subconscious desire to see it go on.

“There’s something to be said for tradition,” said MacLaughlin. “We measure success in those types of terms too. I think we’re trying to equate our streaks in terms of our minor accomplishments with some of those major things, and those aren’t even close to the same thing, but that provides us with the reinforcement we desire.”

In a brief summary, we keep streaks for a multitude of reasons, and we criticize them for several causes as well. Perhaps we have far-away friends that we’re trying to keep in touch with; perhaps, in contrast, we feel that keeping streaks is an inefficient way to do so. Maybe we like to keep them because we like to have some structure in our daily life; maybe, instead, we condemn this kind of structure as a dangerous addiction.

Or maybe, just maybe, we could be expressing our humanity, simply admiring the large number we’ve created with our own actions. We could be creating our own miniature Tower of Babel, a perfectly acceptable and predictable pursuit for a species that loves intangibles. Before you go attack someone who does or doesn’t keep streaks, you have to remember that there’s a staggering amount of complexity in these little numbers and flames. There’s psychology, science, culture, and a whole lot more behind them, and there are both positive and negative consequences as a result of them. So, unfortunately, the question of why doesn’t have an empirical answer for now. If you want to know on an individual basis, though, it’s pretty simple.

Just ask.

Oliver is a senior, and he has been a part of the newspaper staff for 3 years. He covers a wide range of topics, from school news to student features,...